THE PRE-RAPHAELITE GODDESS

During the middle of the nineteenth century, a style of art emerged that was in a striking contrast to the staidism of the age, and which contributed to the re-emergence of the goddess in the western mind: Pre-Raphaelitism. Through this art, the goddess, and in particular, the dark goddess, was manifested at a time central to the spiritual evolution of England, and the world.

The recent history of England is punctuated by periods during which there were resurgence in matter magickal, or during which a new, or rediscovered, way of looking at the world was adopted. There are three such magickal periods in particular, and each was at a time a queen was on the throne. Under the rule of Elizabeth 1 (1533-1603), magick came to the fore in the form of her court astrologer, Dr John Dee. Dee advised Elizabeth on the most propitious dates on which to conduct her affairs, including the date of her coronation. In turn, her matronage allowed Dee to develop and explore his unique system of angelic occultism, Enochian magick, which is still with us today. Such was Dee’s stature that it is widely thought that he was the template -for the magian figure of Prospero in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Shakespeare’s vast corpus, and the hermetically themed Globe theatre, were also part of England’s magickal awakening, as was the work of Bacon; who, to some, was Shakespeare himself.

In our own age, the rule of Queen Elizabeth II has ushered in what has been colloquially described as the New Age. This has entailed a new view of the world in which many forms of, sexuality are embraced where they were once suppressed, whole new forms of science, and a growth in all manner of new belief systems and philosophies. This is not necessarily related to the person Elizabeth Windsor, but to those archetypes she unconsciously embodies; though some embodiments can be more aware of their role than others. Such has been the influence of Elizabeth II that her potential successor, Prince Charles, has promised to be a protector of faiths, rather than a traditional protector of the single Anglican view of the world.

Returning to the nineteenth century, England was ruled by perhaps the greatest monarch in its history, Queen Victoria (1819-1901). While the spectre of traditional Victorian values looms large over this age, her reign was one in which magick enjoyed a revival that carried on well into our own age. In 1888, fifty-one years after Victoria’s accession, what was to later become the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was first formed, while a year later, one Aleister Crowley became an initiate, before he left after a stormy internship to form his own order the Argenteum Astrum. Whatever ones personal opinion on the magick, or worth, of either the Golden Dawn, or Crowley, there is no denying the impact both had on magick, and witchcraft (Crowley having had a large hand in compiling Gerald Gardner’s Book Of Shadows), and it is impossible to ignore the public awareness of magick that they both facilitated.

Exactly forty years prior to the founding of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, eleven years following Victoria’s accession, another order of sorts was formed, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. All young painters, the founders explicitly rejected the conventions of society and art. They deplored the styles of the High Renaissance, and its inheritors, finding more of worth in the early Italian and Flemish art, and in the spirit of, as their name suggests, the artists before Raphael. The art of the Pre-Raphaelites could then be loosely defined as having high definition, bright colour, shallow spaces, and flat plans: Thematically, it dealt largely, although not wholly, with symbolism, creating archetypal images that were direct in their power, rather than simply anecdotal, or descriptive.

Central to the approach was the frequent use of the motifs of poetry, and, indeed, much of Pre-Raphaelitism can be seen as an attempt to do visual justice to the otherwise intangible mental images produced by poetry. Romanticism, from John Keats to Alfred Tennyson, provided a template for the Pre-Raphaelites, and allowed the movement to centre upon the theme it would be most famous for painting, the goddess made manifest in mortal women. These mortal women were models, and sometimes painters in their own right, drawn from the family and friends of the Pre-Raphaelite artists. They were known colloquially as stunners, and amongst their number were women who would come to embody the Pre-Raphaelite goddess: the pale, red-headed, Elizabeth Siddal; the blonde Fanny Cornforth, a former prostitute; the thickly-browed Jane Morris; and the Greek Maria Zambaco. Stunners could be divided into three basic groups: the virgin, typified by Lizzie Siddal; the goddess of sex and desire, embodied in Fanny Cornforth; and the dark goddess of death, typified by Jane Morris.

Of all the Pre-Raphaelite painters, two were particularly responsible for establishing the aesthetic benchmarks of the Pre-Raphaelite style, and for presencing the dark goddess in their work: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and later, Edward Burne-Jones.

ROSSETTI, DEATH, AND THE MAIDEN

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, brother of the poet Christina Rossetti, illustrated the break with tradition that the Pre-Raphaelites represented in his first two major works: The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849) and Ecce Ancilla Domini (1850). In the first, described by Rossetti as ‘a symbol of female excellence’, the artist’s own family was the model for the holy family, with his mother, Frances Rossetti, as Saint Anne, and his sister Christina as the Virgin; ‘her appearance being excellently adapted to my purpose’ wrote Rossetti. The Virgin appears embroidering a red stole with a lily, using a lily in a red jar, clasped by an angel, as the model. The image is one that echoes the art of the middle ages, both in its style, and in its Mariolatry; something relatively alien to the Protestant world of Victorian England. The images of The Girlhood of Mary Virgin recur in Ecce Ancilla Domini, the Annunciation. In this painting, Rossetti premised the directness and force of emotion that would come to typify Pre-Raphaelite art. Instead of a vulgar and clawing sentimentality, Rossetti approached the subject as one of real human emotion, in which the Virgin again modelled by Christina, reacts with shock, and almost fear, at being told she will be the mother of Jesus. The painting is tall and narrow, which adds to the tension of the work, with the Virgin in a white night-gown, shrinking against the wall, while the angel Gabriel floats to the left of the bed. In his hand, he holds a lily which is pointing directly at the Virgin’s womb, and to which her eyes are fixed, almost in dread. That the Virgin is shown seated on her bed adds to the sense of intimacy and realism. The painting is one of vivid human emotion, rather than a simple romanticized or veiled depiction of the event, in which the reality of divine-human sexual intercourse is depicted in all its terrifying potential.

While these early works reflected the light side of the goddess as she appears in New Testament myth, Rossetti also dealt with her dark aspect, Mary Magdalene. The Magdalene was a popular image for the Pre-Raphaelites, as was her province, prostitution, from where many of the artists acquired their models. In 1857, Rossetti painted Mary Magdalene Leaving the House of Feasting, in which she was shown with bare feet, loose hair and a floral crown. The model for Mary was Annie Miller, a model who had been discovered/rescued by the artist Holman Hunt, but who had appropriately escaped from him at the time of the sitting. Rossetti returned to the Magdalene a year later in Mary Magdalene at the Door of Simon the Pharisee, this time using Ruth Herbert as the model, but with the same motifs of wild hair, intertwined with flowers, bare feet, and a palpable sense of erotic power.

Following Rossetti’s death in 1682, his sisters Frances and Christina asked the artist’s assistant and friend, Frederic Shields, to design a memorial window for him in the Kent church where he was buried. Shield’s chose a design based on Mary Magdalene at the Door of Simon the Pharisee, but this was rejected by the vicar as ‘unlikely to inspire devotional thoughts.’ Instead, a work based on The Passover in the Holy Family was used. It is possible to see in Shield’s unconventional choice that Rossetti, and some of the Pre-Raphaelites, were a continuation of the cult of artists through the ages who have venerated the Magdalene as the true expression of the goddess, and the key to any spiritual validity that Christianity might have.

Certainly, the depictions of Mary Magdalene are some of the most powerful of all the Pre-Raphaelite paintings, and they are in keeping with the initiated images of her down through the ages. She appears consistently with long, luxurious red hair, wearing red clothing, with an expression and demeanour of erotic energy, fecundity, and divinity. It is possible to see the Magdalene not only in those paintings that specifically show her, but also in Rossetti’s other celebration of fallen women, such as The Blue Bower (1865), Fazio’s Mistress (1863), and Bocca Baciata (1859). The latter in particular seems like a depiction of Mary Magdalene, the woman depicted being from a tale by Boccacio about a woman with many-lovers whose much-kissed mouth renews its freshness; a stark contrast to the prevailing opinion that promiscuous women were dirty. Such is the archetypal power of Bocca Baciata, where a redheaded woman (modelled by Fanny Cornforth) simply gazes to the left of the viewer, that the pagan poet Swinburne was moved to describe it as ‘more stunning then can be decently expressed.’ While Holman Hunt, whose own painting is more vulgar than erotic, compared it to pornography, and described it as displaying ‘gross sensuality of a revolting kind.’

Rossetti’s Blue Bower, yet again modelled by Fanny Cornforth, was based on the poem Song of the Bower, which he had himself composed, and which reveals several distinctive Magdalenean characteristics:

What were my prize, could I enter thy bower

This day, tomorrow, at eve or at morn?

Large lovely arms and a neck like a tower,

Bosom then heaving that now lies forlorn.

Mary Magdalene was indeed traditionally seen as large bodied (in contrast to the Virgin who appears, like Christina Rossetti, with a slim, almost fecundless body), The simile of her neck like a tower speaks to Mary Magdalene’s association with the symbol of the tower, such as the Tour Magdala built by Berenger-Sauniere at Rennes le Chateau.

Other Pre-Raphaelites dealt with the figure of Mary Magdalene. Anthony Frederick Sandys’s Mary Magdalene (1858-60) shows her as a red-lipped woman, with sharp features reminiscent of Lizzie Siddal (though the model is unknown) and long red hair, holding an alabaster jar to her breast. Dante Rossetti accused Sandys of plagiarism, because of the resemblance to Mary Magdalene Leaving the House of Feasting, but when Rossetti came to paint the Magdalene some twenty years later, it was his painting that resembled Sandys.

Another aspect of the goddess that Rossetti embraced was the death goddess. Death was an important theme for both the Pre-Raphaelites and the Romantics, and the Rossettis were a part of both worlds. The melancholic Christina was able to sum up this emotion towards death, and seems to channel the very spirit of death in her sparse, but beautiful, Songs:

When I am my dead, my dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree,

Be the green grass over me

With showers and dewdrops wet,

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget

Swinburne, on the other hand, wrote of death as Persephone: "Pale, beyond porch and portal, Crowned with calm leaves…Death-like, she has languid lips and cold immortal hands.” He was echoed, in turn, by the Decadent poet Arthur Symons, who enquired:

O pale and heavy-lidded woman,

why is your cheek

Pale as the dead, and what are your eyes.

afraid lest they speak?

And the woman answered me:

I am pale as the dead

For the dead have-loved me,

and I dream of the dead...

For Dante Rossetti, the death goddess became manifested in two models: Elizabeth Siddal and Jane Morris. The dark, naturally chthonic face of Jane Morris made her the perfect model for his Proserpine (1873-77) in which the classical goddess of the underworld is dressed in a dark blue dress, while holding an open pomegranate towards the viewer. Rossetti explained how she was represented in a gloomy corridor of her palace, with the fatal fruit in her hand. As she passes, a gleam strikes on the wall behind her, admitting for a moment the light of the upper world.’ For Rossetti, the image had a second meaning, as he was in love with Jane, who spent the winter months in London with her husband William Morris, but modelled for him in the summer at Kelmscott Manor.

Rossetti used Jane Morris for other classical incarnations of the goddess. In Pandora (1869) she appears as the goddess of the title, bearing the casket out of which flow all the world’s evils with a ruddy glow. In contrast, Astarte Syriaca (1877) celebrated Jane Morris as the eternal feminine, as the goddess who provided the source for Aphrodite and later goddesses. Unlike many of Rossetti’s works for which she modelled (in which she gazes just to the left of the viewer), in this she looks straight out of the centre of the painting. She is dressed in a green, almost aqueous, gown, while she is flanked by two female spirits or aspects that hold torches and gaze upwards. The painting is a sublime visual realization of everything the artist expressed in his accompanying sonnet:

Torch-bearing, her sweet ministers compel

All thrones of light beyond the sky and sea

The witness of Beauty’s face to be:

That face, of Love’s all-penetrative spell-

Amulet, talisman and oracle-

Betwixt the Sun and Moon a mystery

That Rossetti worshipped Jane Morris herself as a goddess is evidenced by the way in which he returned to her image, painting with little variation and little symbolism other than what was implied In titles like: Silence, Reverie, Aurea Catena, The Day Dream, Perlascura and La Donna della Fiamma. But although he worshipped Jane Morris in his later life, the goddess of his younger years was Elizabeth Siddal.

Rossetti had been named Dante by his father who was obsessed with the poetry of Dante Alighieri, and the esoteric meanings behind the Divine Comedy. Naturally, the young Rossetti came to identify himself with Dante, and in turn, identified Elizabeth Siddal with Beatrice, Dante’s mystical and unattainable lover. This was cemented in some of the early works for which she sat: Beatrice Denying Her Salutation (1851-52), and Dantes Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice (18531. But being the incarnation of an archetype risks all that that archetype embodies, and in 1862, after a stillbirth, she died of an overdose of laudanum.

Rossetti’s sorrow and guilt (guilt that was doubled where Lizzie’s grave was exhumed years later to retrieve a book of his poems) led to his most sublime vision of death: Beata Beatrix (1864-70). Lizzie is shown as Beatrice at the moment of death, with her eyes shut, and her gaze directed upwards. She is lit with a rosy golden light, while a red bird drops a poppy into her clasped hands. Rossetti described the moment as a “sudden spiritual transformation. Beatrice is rapt visibly into heaven seeing as it were through shut lids. ‘ In the distance, Dante gazes at Love, ‘in whose hand the waning life of his lady flickers as a flame. On the sundial at her side the shadow falls on the hour of nine...”

The painting is one of the transcendent role of death, where through the opiate gift of the dark goddess, Lizzie has become death herself. She has passed from the role of a mortal muse, to an immortal archetype. Intriguingly, years after the painting of Beata Beatrix, an over-painted photograph of Elizabeth Rossetti (as she was then known) was discovered, in which she is in a similar posture, with her eyes shut, and her hands clasped. Although there is no firm evidence, it would seem that this posthumous portrait provided the template for the larger painted tribute.

BURNE-JONES, SANDYS, AND THE WITCH-GODDESS

While Rossetti found his goddess in the dark browed Jane Morris, Edward Burne-Jones found his in the equally dark Maria Zambaco, who was to typify his work as Jane Morris typified the work of Rossetti. While Rossetti’s style could be described as a style of flesh, in which the strength of full-figures is celebrated, and one can sense the blood flowing beneath the skin, Burne-Jones’s style is one of spirit, in which the human figure is so highly polished that it is the soul rather than the body that seems to be on display. His painted figures possess a luminescence that is almost indescribable, and a fragility that is only just prevented from lifting off the page.

Many of Rossetti’s themes were repeated by Burne-Jones, such as his Annunciation (1879), which echoes the thin design and positioning of Ecce Ancilla Domini, but lacks the tension, energy, and iconoclasm of Rossetti’s original. Instead, it is in his own thematic strain that Burne-Jones truly excelled: the mythic witch-goddess or sorceress. Although vilified by the rest of western culture (even by many that seek to reclaim the feminine), the witch-goddess was understood by Burne-Jones as an essential aspect of the goddess. Writing in reference to Maria Zambaco, who presenced so many forms of this dark goddess, he said: ‘Don’t hate, some things are beyond scolding - hurricanes and tempests and billows of the sea - it’s no use blaming them... No, don’t hate.’

His depictions of Nimue in The Beguiling of Merlin (1874), or Circe from 1868, or Hela as Frau Venus in Laus Veneris (1869), are, thus, never grim demonifications of the goddess, but instead almost reverential celebrations of her divinity and energy. The same can also be said for the sorceress-themed paintings of Anthony Sandys, who owes more in style to the shallow-spaced and full-bodied style of Rossetti, than to the fragility of Burne-Jones. The sorceress is shown with reverence, while still retaining a sense of danger, in works like Medea (1868), Medusa (18775), Vivian (1863), and Morgan le Fay (1862). Appropriately, the model for Morgan le Fay is said to have been a gypsy woman called Keomi, who was Sandy’s mistress in the 1860s, and who can also seen as the model for Medea.

THE PRE-RAPHAELITE SISTERHOOD

For a movement that celebrated the goddess, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, appropriately, had a number of notable women artists amongst its number. Several of the most famous models were artists in their own right. Lizzie Siddal was encouraged by Rossetti to paint and draw, and was taught by Rossetti himself, which led to their engagement. Marie Spartali Stillman, who posed for Rossetti, Burne-Jones, and Julia Margaret Cameron, and made Swinburne wax ‘She is so beautiful that I want to sit down and cry,’ was an artist of some note. Her Convent Lily (1891) combines Rossetti’s shallow-spaces with the luminescence of Burne-Jones, and yet is wholly her own.

Jane Morris and her sister Elizabeth Burden became renowned for their embroidery, going so far as to unstitch old pieces to learn how the stitches were laid. Jane’s husband, William Morris, created a company Morris and Co, which dealt with tapestries and stained glass, and Jane and her sister created many of the works; although William Morris was given the credit for commercial reasons. Of specific note are three panels produced during the 1880s, one of which is the striking depiction of the Amazon queen Hippolyta. She is dressed in a full suit of armour, beneath a tapestried robe, with a sword and spear, and a face rather reminiscent of Jane Morris. Two of the true giants of the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, though, were Evelyn de Morgan and Julia Margaret Cameron.

The growth of the Pre-Raphaelites coincided with the emergence of photography as a genuine art form, and Julia Margaret Cameron was at the forefront of this revolution. Many of the elements of Pre-Raphaelitism can be seen as consequence of photography, in particular the shallow-spaced portraits of Rossetti. Beata Beatrix is certainly anticipated in Cameron’s Call, I follow, I follow - let me die (1867), which depicted Elaine from Tennyson’s Idyll as a woman’s head in dramatic profile. The image can also be seen as a prototype of the head of Nimue in Burne-Jones’s The Beguiling of Merlin (1873). Cameron was in turn no less influenced by the poetic nature of Rossetti’s painting in developing her unique photographic style. She returned to Elaine in the more literal Elaine the Lily Maid of Astolat (1874), and the whole Arthurian cycle, particularly as described by Tennyson, became her source of inspiration.

In the 1870s, Cameron began a full series of photographic images based on the Idylls of the King, with models dressed in believable period costume, and mirroring the themes other Pre-Raphaelites would render in paint or tapestry. Her images are, in many ways, the definitive interpretations of Tennyson’s work, having all his mystery, but underscored with a palpable sense of the human. The same is also true of her other photographic renderings, such as the Marie Stillman-modelled Hypatia, The Spirit of the Vine (1868), and Mnemosyne (1888).

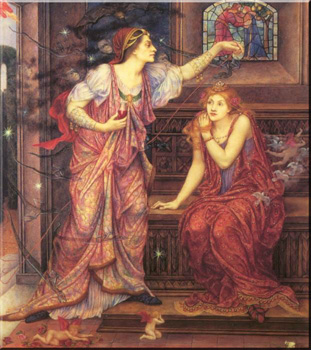

The magick of medievalism was also explored by the late Pre-Raphaelite, Evelyn de Morgan. De Morgan’s style can be compared to that of Burne-Jones, with a similar luminescence and lightness of feel, but with a more endearing quality of her own; Burne-Jones slight figures are often more disconcerting than friendly. She also celebrated the witch-goddess as Burne-Jones had done. In her Queen Eleanor and Fair Rosamund (1888) she illustrates the historical incarnation of Hela as the queen of Henry II about to poison Henry’s mistress Fair Rosamund within her labyrinthine bower (a reiteration of the ancient pagan myth of the goddess in the labyrinth). The painting is remarkable not only for its ability to grasp the defining moment (an epiphanous moment akin to Rossetti in Beata Beatrix), but in de Morgan’s unique style of translucent dragons and cupids, which flit above the plain of the image.

These same ephemeral dragons appear in The Captives of the same year, in which five young women are trapped in a subterranean cave, while dragons float around and through them. It has been suggested that this image was a scathing comment on the Victorian restraints on women, and de Morgan was certainly not someone who was willing to submit to a role. As a student, at the Slade School of Art in London in the 1870s, she had rebelled against the prevailing belief that art should be a hobby for womyn, rather than a serious occupation, and resented the convention that young womyn should never venture out unaccompanied. She consistently tried to evade her chaperons, and would paint in secret when otherwise forbidden to.

If Jane Morris can be seen as a persistent symbol of the Pre-Raphaelite goddess, it is apt that Evelyn de Morgan chose, between 1904-1905, to paint her in her crone phase for The Hour Glass. Jane was shown as a sombre queen, sitting on a throne, her hands resting upon an hour glass; with motifs indicative of Jane’s personal love of music, and skill in tapestry, in the back ground. The image is one of time’s passing, and in many ways marks the end of the century, and the end of the Pre-Raphaelites. Jane Morris in her old age is still very much the dark goddess who gazed out from some many of Rossetti’s paeans to her, and simultaneously, she becomes all the other Pre-Raphaelite women in whom the goddess manifested.

* * *